Why Isn’t Country History Taught During Black History Month?

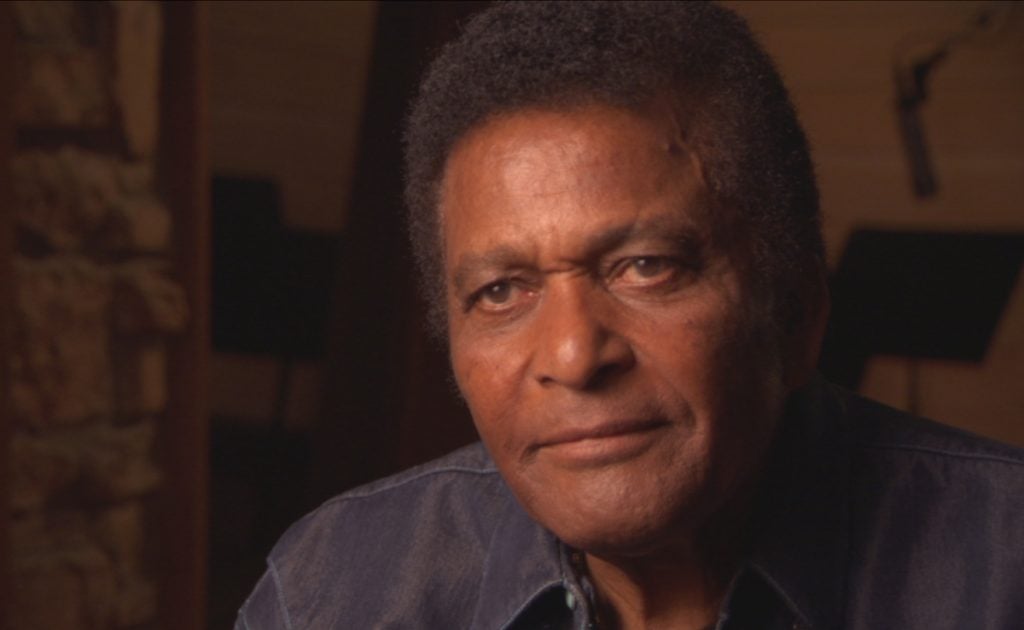

The call Charley Pride the Jackie Robinson of country music. But why don’t they call Jackie Robinson the Charley Pride of baseball? Both country music and baseball are iconic American cultural institutions. Somewhat ironically, Charley Pride also was a baseball player, playing in the Negro leagues before making it to the minors and helping to integrate baseball just like he did country music. Pride also owned a minority stake in the Texas Rangers baseball team for a spell.

But we don’t talk about Charley Pride’s legacy of helping to integrate country music in Black History Month curriculum, do we? We don’t talk about Pride’s 29 No. 1 songs during his Hall of Fame career, or how he was the fifth ever CMA Entertainer of the Year in 1971, and the first to win the CMA’s Male Vocalist of the Year back to back.

When Black History Month in the United States comes up every February, we also don’t talk about how harmonica maestro DeFord Bailey was arguably the first ever Grand Ole Opry performer, and a huge part of the show’s cast early on. We don’t talk about how Ray Charles didn’t have just one country album that helped sell the virtues of country music to a wider audience, but seven of them, and just like DeFord Bailey, how Ray is in the Country Music Hall of Fame.

We don’t talk about the Hank Williams mentor Rufus “Tee-Tot” Payne, or Leslie Riddle who worked with The Carter Family, or Linda Martell making her Opry debut and her great country album Color Me Country, or Stoney Edwards, or the other great legacy country artists who happened to be Black.

If you grew up in America, you knew the drill every February in public school. Here came the same top line Black American icons whose name you can recite like your multiplication tables: Martin Luther King, Rosa Parks, Harriet Tubman, Fredrick Douglas, Muhammad Ali, Jackie Robinson, Willie Mays. “George Washington Carver invented the peanut” is the old joke, because that’s what would be ram rodded down your throat as an American kid every winter to the point where the anecdote became trite.

You’re even likely to learn about important American music artists such as Louis Armstrong or Chuck Berry during Back History Month.

But unless your teachers were willing to buck the published material on Black history, country music was never mentioned. And don’t go accusing this observation as being “woke.” If Black History Month already happening (and it is), country music should be part of that basic, elementary/middle school-level syllabus. And for some reason, it’s not. It’s curiously excluded.

Over the last decade or so, there has been a culture war and reckoning in popular culture and Academia about the proper place of Black performers in country music. This has been spurred in part by high profile “country” moments from Lil Nas X and the song “Old Town Road,” as well as Beyoncé’s recent album Cowboy Carter. To certain activist voices, these artists were exposing the erased history of Black people in country music. It was often proceeded by the bold proclamation, “Don’t you know the banjo originated in Africa !?!”

But of course the banjo originated in Africa, and you won’t find a history book that disputes that, or the importance of Black artists to county music. The problem is not that the historical record of country music is wrong or that it erased its Black legacy as Saving Country Music recently illustrated. It’s that public perception is that country music is solely the domain of White people and always has been. But that perception has always been wrong, and education should be there to set it straight.

Before the early 1960s, the banjo wasn’t only synonymous with Black culture, it was often used as a racist trope against Black people. Before things like the TV show The Beverly Hillbillies and the theme song “The Ballad of Jed Clampett,” (which was a big hit), as well as the “Dueling Banjos” scene from the film Deliverance, and the syndication of Hee-Haw, people thought of the Banjo primarily as an instrument of Black America.

The Black history of country music wasn’t erased, it was just forgotten. And part of the reason for this is the proponents of Black History Month just did not bring up country music as part of that initiative. Black History Month officially started in 1970. That was just before Charley Pride’s top prominence, though Ray Charles had already released country records, and the banjo’s origin story was well-documented.

And now instead of working to re-awaken this Black legacy in country and put it back in its proper place, we’ve seen the pendulum swing the complete opposite direction in some circumstances, with some outlandish statements presented to the public about how country music has always been solely Black music that was stolen by White people—and despite the clear Scots Irish influence via Appalachian immigrants—White people have no real agency in country music whatsoever.

Just watch the trailer for the recent documentary High Horse: The Black Cowboy to see the kind of hyperbole that is employed in the service of attempting to take over country music and cowboy culture at large from White people as opposed to simply trying to share in its bounty and legacy.

The assertions for High Horse: The Black Cowboy are just as false and dangerous as saying Black people had no hand in the formation of country music at all. And while these radical proclamations are presented as challenging racism, it actually stokes racism because they’re built off of false pretenses, and presents the stakeholdership of country music as a conquest where it’s winner take all based on race.

As opposed to attempting to “take over” country music from White people, how about we all just agree that a basic, baseline level of country music history should be taught in schools that talks about Charley Pride and things like the origins of the banjo. That way all Americans understand they have a legacy in country, and the agency to enjoy it and be a part of its community if they so choose.

It’s not that country music has erased the Black legacy from the genre. It’s that country music was erased from Black History. Just as we all have a hand in country music, we should all have a hand in making sure the youth of America are properly educated about the Black role in country. And no, that role is not that Black artists created the genre and White people stole it. It’s also not that it’s only White people’s music, with a few token Black contributors. Country music is a melting pot, with Hispanic, Hawaiian, and other influences in there as well.

It’s true that especially over time, White people have been the predominant proprietors, stars, fans, and influencers of country music’s lineage beyond its origin story, just as Black performers have been the primary contributors to blues and hip-hop. And there’s nothing inherently evil about that. Music is an expression of people’s culture often tied to race.

But history teaches us that country music is for everyone, and by everyone. Or at least it should.

– – – – – – – – – – –

If you found this article valuable, consider leaving Saving Country Music A TIP.

January 28, 2026 @ 12:40 pm

How often is country music even mentioned in any sort of American history class, other than one focusing on popular music? What I recall of my high school American history classes in the early ’70s was plenty about presidents and other politicians, wars (especially the Revolutionary and Civil wars), the emancipation of the slaves, westward expansion, the Depression, immigration, and the social unrest that started in the ’50s. Nowhere was any music or musician mentioned. Just as there was no mention of Duke Ellington or Ella Fitzgerald, there was also no mention of Hank Williams or Frank Sinatra.

When black contributions to American history were brought up, the names were usually those of George Washington Carver and Booker T. Washington, and maybe Jesse Owens from the sports world. Is popular music now an important part of standard American history teaching?

January 28, 2026 @ 12:49 pm

Obviously, popular music is not part of regular grade school curriculum. Neither is sports. But all of these things are broached in standard Black History Month curriculum. I looked through some standard syllabus’ while researching this article, and like I said, you saw stuff about Louis Armstrong, Chuck Berry, etc. But there’s nothing about Black country artists. I think the reason to underscore the importance of this is because there’s a misconception that there are NO Black artists who ever made country music until Beyonce or Kane Brown or something.

January 28, 2026 @ 2:39 pm

Music was never taught when I was in high school in Indiana 2000-2004. There was a history teacher that made us watch certain classic movies and he had this thing in his class where he would only play music from 1969 and back. It really is teachers like that who have this sort of impact on some students. Directly shoving students nose into something will cause most to not care and disregard it but if it’s presented passionately and not as direct schoolwork it can resonate.

January 28, 2026 @ 1:20 pm

Simply out, it does not fit the woke narrative.

January 29, 2026 @ 9:44 am

You are right. The wokes are trying their damndest to make sure blacks are erased from country music. Unfortunately it got in the way of putting kitty litter in schools, and changing weather patterns. There is only so much time in the day, which is why we ended up with Kane Brown.

February 3, 2026 @ 6:18 pm

The ‘wokes’ have got nothing to do with this aside from the fact that people like you just want to harp on anybody progressive, and deny progress because you can’t handle any.

January 29, 2026 @ 11:51 am

Highlighting black contributions definitely fits the “woke” agenda which I whole heartedly support.

January 28, 2026 @ 1:24 pm

All true. I think our school history curriculum is lacking in general. It tries to cram as many dates and names as possible in a small amount of time and causes kids to tune it out. If real context like music was used more often to trace issues through history, more people may study it. Part of the reason we keep repeating mistakes from the past. And believe it or not there are areas of the country that refuse to acknowledge Black History Month at all.

January 28, 2026 @ 1:40 pm

I am more than fine with my children not learning about country music in school. Regardless of who sings it.

I also think the cultural impact of Jackie Robinson was far greater than that of Charlie Pride. One of many reasons for this is because we celebrate firsts. Robinson was the first black man to play in the major leagues (as a black man, others were able to pass (Babe Ruth), or pretend to be Native American or whatever), Charlie Pride was probably the first black man with a number one country record or something, but he clearly wasn’t the first to perform, or be on stage , or even be at the Opry.

January 28, 2026 @ 2:05 pm

I would agree that Jackie Robinson’s cultural impact was greater. My only point is that if we’re releasing multiple documentaries about how the Black legacy in country music was erased from history while every history book makes that legacy clear, who exactly is doing the erasing? And if people both White and Black are unaware of Black country music artists, what can be done about it? Simply proclaiming country music is 100% Black and always has been is not real solution.

January 28, 2026 @ 4:24 pm

I’ve never seen this written anywhere, but I’ve always felt that the great Tennessee Ernie Ford had some black in him. If you see photos of him in his heyday, he looks like Adam Clayton Powell.

I also think that Tennessee Ernie’s sound has a strrong black influence.

Listen to his brilliant, iconic recording of “Sixteen Tons.” Near the first minute mark, he sings

“I loaded sixteen tons of Number 9 coal/

and the straw boss said ‘Well, bless my soul.'”

Ernie adds an effeminate lisp to the the Merle Travis lyric when it comes to the straw boss. He just about sings “bleth my thoul,” with a bit of a twinkle in his delivery–a common black, comedic way of ridiculing someone.

The straw boss’s lisp is prominent on the original recording, but Ernie seemed to tone it down a notch when doing a video performance of the song for his national TV program.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RRh0QiXyZSk

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pLVtJkpl_ug

[It wan’t an exclusively black thing. The Texas born 1970’s NWA pro wrestler Dusty Rhodes–who was white, but affected a black vernacular, famously used to talk that way when in character.]

January 29, 2026 @ 9:57 am

Interesting. I know very little about him beyond that song. But I think a lot of us, and a lot of famous white people of the past probably have/had more black ancestery than we’d guess. I am not a sociologist, nor am I from the south, and I wasn’t born until the 80s, but my guess is what we see as “black vernacular” from that time and place just might be “poor vernacular”.

January 28, 2026 @ 4:31 pm

The only other black performer at the Grand Ole Opry or in country music period prior to the arrival of Charley Pride on the scene was DeFord Bailey in the 1920’s and 30’s; Charley was the first one to become a bona fide superstar, so his rise in the country music field is even more significant

January 29, 2026 @ 9:53 am

More significant than Jackie Robinson? Maybe more rare, or more impressive, but not significant. Country music of the 70s didn’t have the cultural cache that baseball of the 40s did. People didn’t go to Charlie Pride concerts to the purpose of heckling and throwing stuff at Charlie Pride. Kids didn’t grow up dreaming of being country musicians the way they did baseball players. Being a black astronaut is cool too, but most people don’t give a shit, which is why I can’t tell you a name of a black astronaut. Maybe if Al Green made a song about him I could, but I can’t.

January 28, 2026 @ 1:53 pm

Tina Turner’s first two solo albums, Good Hearted Woman, and Tina Turns Country On are both very good. I like the second one better. It is produced “more country”. But Good Hearted Woman is a record made up of country songs, produced fairly country.

January 28, 2026 @ 2:43 pm

I did not know that. Always been a fan of hers. Will have to dig in to those recordings. Thanks for the heads-up.

January 28, 2026 @ 3:21 pm

Did a whole article on this when Tina Turner passed.

https://savingcountrymusic.com/tina-turners-southern-soul-and-country-contributions/

January 29, 2026 @ 9:54 am

Sweet, thanks, look forward to reading that!

January 29, 2026 @ 11:27 am

Jackie Robinson was not the first black man in the MLB. That was Moses Walker. Jackie Robinson was the first black man in the modern era of MLB. Black people were in the mlb in the 19th century; they were also in Winter League in the 20th Century associated with the MLB but not technically in it. Robinson broke that barrier.

January 29, 2026 @ 11:40 am

Yeah I know. I also think a lot of the black dudes in the winter leagues in the 20th century were claiming to be latinos. Also, most of the winter leagues were in latin countries, the California one being the exception.

January 28, 2026 @ 2:22 pm

Black people were foundational in American music in general. The overwhelming majority of millennial and younger black people today don’t listen to Country, Jazz, Blues, etc….only stupid ass rap music. That’s why. They need to set down every black student and force them to listen to Howlin’ Wolf, Miles Davis, Charlie Pride and Ray Charles. (to name a few)

February 3, 2026 @ 9:21 pm

Why? So that you can alienate them further? That won’t work as a way of teaching said history, and you know it; your saying that only shows how white people such as yourself love to bash rap, and have always bashed it even before it was ‘gangsta’. You sound like every other older white person who despises contemporary black culture (and black people) while pretending to like them.

January 28, 2026 @ 2:37 pm

Cmon Trigger– why isnt black country music taught during black history month? You know why we know about many of the famous figures we study during black history month? Because theres a movement to make sure those people are recognized amd remembered? Who is leading a collective effort to commemorate black country artists? The CMAs? Nope. So it absolutely is on country music if they want more recognition of black artists to lead the charge, but half of country music is too busy complaining that black artists are being even nominated for country music awards so I dont think thats gonna change any time soon. And no, the presence if Charley Crockett, Mickey Guyton and Darius Rucker doesn’t make the black community forget the stink yall threw about Beyonce, Lil Nas X, or Shaboozey.

January 28, 2026 @ 3:29 pm

“Who is leading a collective effort to commemorate black country artists?”

Well, that is kind of my point. That is why I posted this article. I’ve posted articles on Stoney Edwards, Tina Turner, Ray Charles, Charley Pride, Linda Martell, Rufus Payne, DeFord Bailey, etc. that could be easily turned into academic lessons. One issue the “collective effort” that seems underway is things like “High Horse: The Back Cowboy” that is only interested in reclaiming country music from White people since it was stolen, which in turn makes their efforts basically inert, if not counter-productive, because it’s too radical, controversial, and frankly, untrue to turn into curriculum aside for race studies classes in Universities.

You want to change the misconception that country music is only for White people? Tell the story of Charley Pride, and dispel that misconception.

January 29, 2026 @ 7:31 pm

Black slaves got their music from Classical music, and combined it with African music, and in that combination created modern hymns, jazz, and blues. Appalachians in turn took that combination and created bluegrass; and Southerners (of all ethnic backgrounds) in turn took that music, and created modern Country music. It belongs to everyone not more one or the other, or just one group of people: it belongs to all of us.

January 28, 2026 @ 4:38 pm

The difference is, Darius, Charley Crockett, and Mickey Guyton are actual country artists compared to Beyoncé, Shaboozey, or Lil Nas X; I personally would never throw shade at any of the former as they make genuine country music. So that’s an apples vs. oranges argument

January 28, 2026 @ 5:34 pm

And Beyonce said, “This ain’t a country album.” It was never meant to be a country album. Calling it a country album is an insult to Beyonce’s artistic intent. It’s a total distraction from the underlying issue.

January 28, 2026 @ 8:32 pm

No Darius, Charley and Mickey are country singers in a subgenre of country that seems to have gatekeepers (like on this site) whose walls around the genre seem specifically designed to keep out black artists influenced in part by modern black culture. It is unconscionable for any observer not so singularly devoted to keeping a “traditional” view of country music to suggest Shaboozey isnt a country artist. This isnt new by any means, a less glorified view of country music than this article would point out that since the 1920s, Country Music producers found value in separating Hill Billy music from Race records… if were going to demand we plaster Charlie Prides name everywhere, we might as well be honest about the historical racist roots of the genre. In addition, the article goes into a long history of how the banjo, but again, there is a long lineage of black country blues and delta blues players that get ignored here and everywhere else. You’ll never find an article about a Keb Mo release, or Jontavis Willis or Eric Bibb or Amythyst Kia or Kingfish news on here…

So there are plenty of black country artists who get ignored by SCM and mainstream country because their version of country doesnt involve pick up trucks or Telecasters, and so the artificial constraints that country music loves so much more than other genres shuts them out.

And while I guess it doesn’t matter, but when less than 3% of music played on country radio is from black artists, shouting “But CHARLEY PRIDE!” reeks of tokenism (as Jason Isbell has pointed out before much to Triggers consternation). Either way if you really wanna make it a thing, make it a thing, but just know country music has failed black artists and black culture, not vice versa

January 28, 2026 @ 9:15 pm

Mike,

I have no idea what you’re talking about with this comment, and I don’t think you do either.

“So there are plenty of black country artists who get ignored by SCM and mainstream country because their version of country doesnt involve pick up trucks or Telecasters…”

“And while I guess it doesn’t matter, but when less than 3% of music played on country radio is from black artists, shouting “But CHARLEY PRIDE!” reeks of tokenism”

Are you kidding me? Did you really just compare Saving Country Music to Bro-Country and mainstream country radio, two things this website was founded to deconstruct? The entire point of this article was to say that we should teach that Black people have agency in country music as part of Black History Month. And no, I’m not just saying Charley Pride. I named off multiple artists and influences in this article alone. I am saying if you’re not even going to teach about Charley Pride during Black History month, the false notion that there are no Black people in country music will persist.

Also, the hillbilly vs. race records thing is an internet canard. The reason hillbilly and race records were separated is because at first they were lumped together in the great othering of rural music. Also, that was over 100 years ago, so probably not relevant to today. But yes, you could teach about that during Black History Month. Or, just keep teaching how George Washington Carver invented the peanut K thru 12. I was just trying to address the issue constructively, which for some reason in your comment you seem to be accusing me of getting in the way of.

January 29, 2026 @ 6:11 am

First off… George Washington Carver didn’t invent the peanut, he just created new uses and cultivation techniques for it.

But the point is when the industry puts up walls that seem to target black artists who want to play country infused with their cultural influences, or send other black artists who play delta or country infused blues to a niche status, you end up naturally excluding a lot of ways in which black artists can influence the genre. Country isn’t alone in this, rock, Americana and even Blues all suffer from a lack of black audiences, but let’s face it, there are a lot of country music fans who view country music as a vessel for white (primarily southern culture) who will accept a few black artists so long as they fit a comfortable traditional mold, and those fans have pushed back when black artists try and infused other traditions into the music (which was the point of Beyoncés “not a country album remark but thats for another time)

And obviously I know SCM isnt a purveyor of bro country or a supporter of some of Nashvilles most regressive tendencies, but some conversations about why there arent more black artists in country involve uncomfortable conversations some of which you bristled at when Jason Isbell tried to bring them up when this stuff was more at the forefront of people’s minds. Separating Hill Billy and Races records is not an internet canard its been well documented how it led to Black Artists getting less exposure, and it is part of the roots as to where we are today. Nor is it canard to suggest that there are issues that suppress black participation in country music.

My point of all of this is instead of asking why Charley Pride and a tiny handful of other artists arent recognized for their contributions to an industry that still by-and-large excludes black audiences and artists, and instead ask how country music can better remove barriers for black artists who are blending their history and culture into the music, which would lead to a lot more historical recognition, and a richer tapestry of music to boot.

January 30, 2026 @ 10:41 am

The marketing of roots music as “Old Familiar Tunes” “Old Time Music” or “Race” is more nuanced, complicated and interesting than most are aware of. The country was and is intensely racist, no doubt, but the record companies were more interested in selling records than segregating sounds. White musicians appeared in Black labels and catalogs and vice versa. Tejano artists were released in Cajun and Ukrainian catalogs. White country artists were marketed in Mexican catalogs. Advertising of the era often paired Black and white country and race artists in the same physical catalogs showing that the labels understood that there were significant similarities and overlapping interests in the music. Other catalogs listed country, race, Mexican and Cajun music in the same release. The main goal was selling records and lots of consumers in those days had interest in and purchased music from across race and ethnic catalogs.

January 28, 2026 @ 2:51 pm

Speaking of black music and the banjo, check out mento. It’s Jamaican folk music that inspired the ska and then reggae genres. The Jolly Boys are the most famous, with recordings still available. Highly recommend!

January 28, 2026 @ 4:21 pm

We’re doing a show tomorrow night on our station playing some music from local country artists and regional country artists from years past from all around Ohio. I’ve been scouring the internet, Ebay, and local vinyl record stores to find as many artists from Ohio I could and learn as much about them as I can. I was surprised to find out how many black country performers there were in Ohio in the 1960’s and 1970’s.

A quick story about one of them from Cincinnati Ohio. His name was Otis Williams (not the same Otis Williams from The Temptations). He had a doo wop group called The Charms based out of Cincinnati.

He later decided to take a break from music and became a barber in Nashville. He met producer Pete Drake while there, who bet Otis that he could not record a country music album that would sell or do well on the charts. So, Otis recorded Otis Williams and The Midnight Cowboys in 1971. The Midnight Cowboys were a fictional band billed as all the members being black. It was an album of mostly all covers, a couple of those being Charlie Pride songs.

The album is on Youtube if you want to check it out, I think it’s a pretty good early 1970’s country album

January 28, 2026 @ 6:39 pm

Ben,

I too am an Ohio guy and I collect vinyl records. Lots of country of course and im always chasing Ohio artists in particular. You familiar with Doug Jones from Chillicothe ? I’ve got an autographed copy of his first album. It didn’t sell well. He was a man of color and a decent country singer. He did have a ringing endorsement from Pee Wee King who discovered him. He was very influenced by Charley Pride, played for years around Ohio but didn’t make the big time. Very country voice and music undeniably traditional. His album is on YouTube. Look him up. If your interested I know where a copy of his first album is for sale. Just saw it in a shop a couple weeks ago.

Always thought Otis Williams was the one from Temptations. Hmmm.

January 29, 2026 @ 4:19 am

I did come across a couple of his songs on Youtube, but I wasn’t able to find out much info about him. I’d definitely be interested in getting one of his albums.

If you’re into Ohio country music history, I talked with an author from Greenfield, Ohio earlier this week. His name is Eric Grates, and he has a book coming out in April called “The Notorious Adams Boys.” Don Adams is the last surviving brother, and Eric has spent the last year or so talking with Don getting info for the book. He has some very interesting stories he shared with me on the phone. It’ll be a good book.

January 29, 2026 @ 6:45 am

Ben, call up Apollo Records in Chillicothe, they have a used copy of Doug’s first album. Its got extensive liner notes on Doug. I had asked Don Adam’s about Doug Jones, and he definitely remembers him, though he never played any gigs with him. He was a regional act around Ohio, but he had tested the waters in Nashville and never got anywhere. I’ve thought about looking his relatives up sometime, who knows maybe I’ll do more research.

Yes, I knew the Adams Brothers, I did a few articles on them on SCM. Eric Grate and I spoke this past year at length about his book. Don’s dying of cancer, so Eric’s writing with urgency.

February 1, 2026 @ 9:05 am

Thanks. I’ll try them. I had no idea Don was in such bad health. Prayers to his family today.

February 1, 2026 @ 9:24 am

Ben, update: Don Adam’s passed away this morning. Stay tuned, will have an article on him ASAP.

January 28, 2026 @ 5:16 pm

The truth isn’t nice. Black History Month has been hijacked by critical theory people.

For those people, the truth isn’t objective. It’s “my truth” and “your truth.”

In their version of truth, country music isn’t a legitimate art form. It’s just rednecks saying racist stuff. The objective truth means nothing to them if it doesn’t fit their version of the truth. The black artists who are forgotten aren’t worth their time if they don’t fit the narrative.

Does that sound overly simplified? It should, but if you work with enough of these shitheads long enough, you’ll understand their flawed logic. That’s how they think and act.

January 28, 2026 @ 5:35 pm

One of the worst couplets in recent American history is “my truth”. My truth doesn’t sound very inclusive either, does it?

It isn’t that overly simplified either. I don’t think it’s understanding the flawed logic as much as it is tuning out stupidity so you don’t end up pulling your hair out.

January 29, 2026 @ 11:59 am

Most that use the term “critical (race) theory” can’t explain it or point to someone who actually supports it. You should probably expand your TV viewing.

January 29, 2026 @ 1:43 pm

The critical theories I’m most familiar with are critical pedagogies, which are more influential in public schools where Black History is taught than critical race theory–which is also used in most discipline matrices. As far as where I get my information, I’ve read Paulo Freire, bell hooks, and several others like them. I also interact daily with “DEI Experts” who are influenced by all manner of critical theories, so I get to see their war on logic and reason firsthand.

I have no idea what “TV viewing” you are referring to, as I don’t watch much.

January 29, 2026 @ 1:45 pm

Edit: CRT is used in most discipline matrices (under the label “restorative justice”) in major urban areas. I doubt rural schools are doing it.

January 29, 2026 @ 2:28 pm

They are. Look at you with your M.Ed.

January 29, 2026 @ 2:31 pm

When I say they are, I should specify, at least they are in blue states, even if the counties are red. About don’t know about rural areas in red states.

January 29, 2026 @ 3:02 pm

I have nothing further to add. I’ve done some study of critical theory, but you’ve got the bases covered.

February 3, 2026 @ 9:34 pm

Said people are only ‘shitheads’ to you because they’re tired of white racism and the crap and stress that it causes black people to suffer, and know how to talk about it better than you. That you can’t get that, or critical race theory, only shows what you are as a person, and why nobody should care about what you say about race relations.

January 28, 2026 @ 7:04 pm

Has Black Opry closed up shop? Their last X post was way back in June 2024 and I haven’t seen much publicity about them since Holly G ran to mainstream media bitching about the Grand Ole Opry allowing Morgan Wallen on stage.

Has Holly G finally realized that it takes a level of talent rather than a type of skin color or sexual orientation for people to like the music?

January 29, 2026 @ 4:10 am

I would like to see Alexander Downing (Big Al Downing) brought up in these discussions. He only had a few top 20 songs including the Iconic hit Mr.Jones that got a lot of airplay in the D/FW region. He was nominated for Most promising new artist on some of the award shows and made the country variety shows, Hee Haw and Pop Goes the Country and more. On my classic country station, 20th Century Country, I have 3 of his songs in the autoDJ mode and have played him live at times. When I first started listening to country music as a teenager I heard Charlie Pride and Big Al in heavy rotation and never assumed that black musicians and influence were ever excluded from country music.

January 29, 2026 @ 7:04 am

Country Music has long been marginalized so it’s no surprise whenever it’s not a part of any cultural discussion. Black History Month is no exception.

It’s unfortunate that Charley Pride does not receive his due for his significant contribution to the genre or for the place he earned in Black history. But the fact is that his well-deserved success did not open the door for more Black country singers. Reasons for that can be endlessly debated but in the end Charley is more of an anomaly than a trendsetter in the history of country music.

To set the record straight, equating the banjo primarily to Black minstrel performers was not a “thing” by the 1950’s & 60’s. I grew up in that era and my earliest memories of the banjo was performances by Eddie Peabody (who played it on many TV variety shows of that time) and numerous country music & bluegrass performers including Grandpa Jones, Stringbean and Flatt & Scruggs. To my recollection any stereotype of the banjo being equated mostly to Black performers had long passed by that time.

Also whenever articles on this site list African-American country performers of the 70’s the contributions of O.B. McClinton are consistently overlooked. Perhaps you weren’t born yet or are too young to remember but O.B. was a contemporary of Stoney Edwards and he actually had a much higher profile than the oft-mentioned Linda Martell. Obie Burnett Clinton charted 15 singles on the Billboard Country Charts between 1972 & 1987. Though he did not score any substantial chart hits he did receive significant country radio airplay for many of his singles that included releases for the Mercury, ABC/Dot and Epic record labels. He died of cancer at age 47 in 1987.

His excellent remake of a 1971 Wilson Pickett pop hit was one of his highest charting singles in early 1973. It was released on the Enterprise label (created as a subsidiary of Stax Records)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ewQsffw5WV0

January 29, 2026 @ 8:55 am

Yes, the banjo/minstrel show stereotype was MOSTLY already dated even by 1945 standards.

A few clarifying points:

Eddie Peabody played the 4-string banjo. The Music of Peabody, Harry Reser and Dan McCall was functionally more comparable to the big band music than the minstrel show music, and the “banjo” as an instrument was already well adopted by this point.

Actually, it would be more appropriate to say that the banjo stereotype ended with the banjo mania of the twenties and thirties, when every instrument was being adapted as a banjo variant for volume’s sake. Banjo-guitars, banjo-mandolins and even banjo-basses really took off during the twenties because they were louder.

Fred Van Eps was already an established 5-string banjo celebrity and there were gentlemans’ banjo clubs for playing what is now colloquially called “classic” banjo style, in reference to the style of music played by (black) Vess L Ossman and (white) Fred Van Eps.

This was BEFORE Charlie Poole and, therefore, BEFORE Uncle Dave, Grandpa and String.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that Charlie Poole was discouraged from recording more banjo instrumentals BECAUSE the companies figured they’d just re-release Fred Van Eps recordings and didn’t expect Poole’s instrumentals to be as popular.

So by the time Earl’s revolutionary banjo style swept the 5-string world, the 5-string had already BEEN the gentleman’s instrument, been superceded by the 4-string and Eddie Peabody style, then experienced a rebirth in popularity.

by the time Earl played the theme song for “Beverly Hillbillies” Vess Ossman’s recordings were 60 years old charlie poole had been gone for thirty years and Dave Macon’s earliest recordings were already 40 years old.

January 29, 2026 @ 1:30 pm

Thanks for that, CountryDJ.

January 29, 2026 @ 9:08 pm

I was going to bring up O.B. McClinton because he got considerable airplay during his unfortunately short career. I remember that he was a frequent guest on Nashville Now and Ralph Emery backed up the fund raising efforts when Clinton was fighting cancer. I also remember that Stoney Edwards had a major label that definitely promoted his career. When I went to see him at the Palomino Waylon and Jessi were in the audience.

January 29, 2026 @ 9:31 am

Also, I can’t stand the overgeneralization of Appalachia that many people do. Appalachia is not a monolith! There is a whole sub-genre of Black Appalachian music that is still being kept alive today by people like Rhiannon Giddens, who you’ve covered extensively.

WBIR in Knoxville did a short story during Black History Month a few years ago about Black influence in Appalachia. The reason I bring this up is that one of the roots of the trope “country music is white” is that people believe all of Appalachia is white! “Appalachia” is a vast region that stretches from New York to Alabama and Mississippi. It covers over 423 counties across 13 states.

I know I’m preaching to the choir on this with you, Trig, because you’ve always pointed these facts out, but this goes hand in hand with what you’re talking about. We should talk more about Nina Simone, Bessie Smith, and Charlie Pride. Anyone with basic historical thinking skills understands that no single group or subset of people influenced the creation of anything.

January 29, 2026 @ 9:45 am

And Great Britain had a black queen some 250 years ago, not to mention the very black Cleopatra of Egypt, known for her milky white skin.

Recent tv shows taught me this.

January 30, 2026 @ 7:14 am

And the European village in the Beauty and Beast live action remake was remarkably diverse for a 18th century setting.

January 30, 2026 @ 7:57 am

being upset over disney remakes is my favorite characteristic of the modern conservative man.

January 30, 2026 @ 11:52 am

I know you are a troll but Walt Disney, the man, was a deeply conservative and patriotic American. Sadly, the modern edition of his company has betrayed his principles.

Pointing out incorrect demographics doesn’t mean someone is upset.

February 1, 2026 @ 6:27 pm

I read something like: most of the leftist discourse is them pretending not to understand. In gentile’s case we can probably skip the pretending part.

February 2, 2026 @ 1:48 pm

Correct, Steven, that is their only tactic.

thegentile has spent years trolling me. It is rather sad.

February 3, 2026 @ 6:26 pm

Wow, so what? Is it hard for you to see people of color in a movie or TV show?

The real ‘troll’ in all of this is you.

January 29, 2026 @ 4:14 pm

I’m guessing for the same reason blues, jazz, rock, folk, polka, ranchero, pop, rap, hip hop, ska, zydeco, and metal aren’t taught during Black History Month. Music is not where the focus goes…

January 29, 2026 @ 5:29 pm

First,about one-quarter of Old West cowboys were black (they were called “cowboys” instead of “cowhands” like white men who did this work because in those days until about 60 years ago,black men of any age were termed “boys” by whites.) This part of Western history was screw-pulously erased by TV and the movies,which buttressed white America’s view of us us simple-minded Negroes who preferred slavery to freedom,and the 50’s were about portraying America as a big WHITE family,with us as menials and jesters.

Second,perhaps blacks,many of whom were and are Country music fans,would embrace our love of Country music and meld it into the Country experience were not (1) Many Country stars of the Civil Rights Era opposed the Movement,ala Marty Robbins,Billy Grammer,etc. and (2) Today’s gatekeeping,which seems to focus on keeping out all but a very few black Country acts.

So Country music,like every U.S. institution,has a very dodgy history with which it largely refuses to acknowledge.

January 29, 2026 @ 8:30 pm

Its always hilarious when we have these articles . It goes from one end of the spectrum to the other. But looking at robinson does teach in ways about country music far as black people go. Sure robinson was a big moment because baseball was in its golden age. Many black people joined him in the majors. But as you look today, not many black people play baseball. You have far more latinos and other cultures as well as whites. Now using a lot of the logic by commenters, there must be some racist agenda but no there is not. Black people started going to football and basketball for various reasons but none of it racist or any other negative conotation. Baseball fell out of popularity. They also didnt really go too much into hockey. They went to sports they enjoyed and the bigger percentage chose basketball n football. Same way goes with music. They went from early country to blues, early rock n roll, soul music,pop, and rap. Sure there are exceptuons but majority went that way. Was it racist.No. it was what they wanted to do. As one style became popular, others chased it. Now over time you develop perceptions where one might find a black person doing country or a white person doing rap or soul as peculiar cause its not the norm but its all fine. But those perceptions remain in all cultures and races. Now today i guess there isnt any new musical areas for people to develop. So there is a lot of people competing for just so much space in each area of music. So you have two things. You have someone like beyonce that just wants more listeners. How does she do that, she does an album that crosses genras. Now someone who hasnt made it in their chosen type of music, tries to go in the country route to get popular enough there to eventually get where they wanted to get to all along or at the very least they get some popularity and some money. The thing is the artist doesnt really get to decide whats country. The listeners do.

January 30, 2026 @ 7:08 am

George Washington’s Birthday should be its own holiday.

January 31, 2026 @ 6:14 pm

It was until 1971.

February 1, 2026 @ 11:51 am

The federal holiday on the third Monday of February is still Washington’s Birthday.

January 30, 2026 @ 8:16 am

Charley Pride was Country music’s first handsome black cowboy,but his good looks were de-emphasized,because,well,they couldn’t have them country gals drooling over a black dude.

January 31, 2026 @ 8:09 am

As someone who lived during the 60’s era I cannot recall Charley Pride’s “good looks” ever being de-emphasized. That was never an issue that I can recall.

What WAS an issue was that he was African-American. His early singles were issued with the name “Country Charley Pride” to underscore his commitment to the genre. RCA initially released no publicity photos of Charley. RCA and Charley’s management were concerned that the good ol’ boys in charge of programming the music for country radio stations in the south would not play his recordings because of his race. The first time most fans became aware of Charley’s race was when they saw his photo on the cover of his 1966 debut album “Country Charley Pride”

To his credit Charley dealt with the race issue head-on with some well-chosen comments during his concerts. To that point here’s some dialogue from his “Charley Pride In Person” live album recorded at Panther Hall in Fort Worth, Texas on June 15, 1968. At that time it was just two and-a-half years after his first RCA Victor single was released so his country career was just gaining traction.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zs2sCPaKmkE&list=OLAK5uy_kR2ciDDbuQGItCKHhkDKiee71pBjHJeqk

January 31, 2026 @ 1:07 am

The only time I heard anything about music in a social studies class was a very little bit about jazz when we were studying the 1920’s. Also had an Egypt obsessed teacher make us watch Aida (not sure of spelling), but neither of those had to do with black history month. I will make sure to ask the pastor of the black church I play guitar at what he thinks about this subject. They did talk about some of the things they were going to be talking about next month but from what I remember it was more regular history and civil rights stuff. Not sure if that is “woke” because like most dumbass buzzwords it has very little meaning as far as I can tell.

February 1, 2026 @ 7:45 am

Charley Pride was extremely handsome,likely the other reason (guess the first?) his picture was kept off his early album covers. Couldn’t have Daisy or Becky wishing they had a handsome black boyfriend….